Background

As outlined in the Introduction page of this website, ecological restoration is a contemporary, systematic method of ecosystem repair. Guided by six practice principles, practitioners implement carefully considered interventions that assist the recovery of degraded ecosystems and impaired ecological functioning.

The goal of ecological restoration is full recovery, insofar as possible… in some cases, constraints

may limit potential to less than full level of recovery. Such cases can still be referred to as

ecological restoration projects as long as the aim is for substantial recovery relative to the

appropriate local native reference ecosystem (SERA 2021: 14).

Dispossession of Australia’s First Nations communities from 1788 and throughout the nineteenth century was accompanied by extensive settler degradation of unique ecosystems. The earliest known attempt by settlers to repair degraded ecosystems occurred in Melbourne, commencing in the 1890s and continuing until the 1920s (see Rehabilitation — Port Phillip Bay 1896). Utilitarian motives predominated, but desire to conserve valued indigenous biodiversity was also expressed. Although the projects are reasonably well documented, there is insufficient information available to justify a claim that they substantially resembled ecological restoration.

Between ca.1930 and aproximately 1980 a number of pioneering Australian settler restoration projects were initiated (Jordan III, Lubick 2011). They featured aspirations, ideals and practices characteristic of ecological restoration. In particular, the projects were highly aspirational, seeking to restore substantial to full levels of ecological functioning. Many projects were innovative, utilised scientific knowledge, and engaged extensively with stakeholders. However, it would appear that Aboriginal peoples and communities did not participate in any of the historical projects.

References:

Jordan III, W. Lubick, G. Making Nature Whole. A History of Ecological Restoration (Island Press : Washington 2011)

SERA (2021) Standards Reference Group ‘National Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration in Australia’ Edition 2.2. Society for Ecological Restoration Australasia www.seraustralasia.com

The earliest historical projects and similarities with ecological restoration — overview

The earliest known Australian settler advocate for holistic restoration of degraded ecosystems was Melbourne journalist and conservationist, Donald Macdonald. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, MacDonald espoused restoration principles that shared many features with ecological restoration. Unfortunately though, opportunities for him to implement a project of this kind did not arise. His story is presented on the Rehabilitation page, in Port Phillip Bay 1896.

The first Australian degraded area repair projects that significantly featured characteristics of ecological restoration commenced in the 1930s. Development of the science, ecology, is likely to have positively influenced the initiation and undertaking of these projects. Also, the 1930s was a period of heightened interest in Australia’s natural resources and their sustainable use, due to concerns about Japanese militarism, overseas expansion and the possibility of war (Griffiths 1996).

Ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful degraded area repair projects were initiated by Australian scientists and conservationists, David Stead and Walter Froggatt. Consistent with contemporary ecological restoration practice, Stead and Froggatt were keen to restore high levels of ecological functioning to their respective degraded sites. Presented here for their historical interest, both of these projects were initiated in the early 1930s.

Dating from approximately 1930, successful arid lands restoration projects conducted in South Australia displayed ambitious revegetation objectives and employed scientifically informed techniques, characteristics typical of ecological restoration. However, few other details about these projects are available, and the sites are no longer identifiable.

The earliest known Australian degraded area repair projects that extensively displayed practices and ideals comparable to the principles of ecological restoration commenced in 1935, at Alstonville on the New South Wales north coast (hereafter NSW), and in 1936, at Broken Hill, NSW. Both of the restored sites persist today.

The Second World War (1939-1945) temporarily halted restoration in Australia. Presented on this page, restoration projects that featured characteristics of ecological restoration emerged in the 1960s, and practice has significantly progressed since approximately 1980, although as illustrated by the entry, Wingham Brush 1980, not without difficulty, debate and even conflict! (McDonald, Williams 2009; Campbell et al. 2017).

References:

Campbell, A., Alexander, J., Curtis, D. (2017) “Reflections on four decades of land restoration in Australia” The Rangeland Journal 39: 405-416

Griffiths, T. (1996) “Hunters and Collectors” University of Cambridge Press

McDonald, T., Williams, J. (2009) “A perspective on the evolving science and practice of

ecological restoration in Australia” Ecological Management and Restoration 10:2 (August)

David Stead, Walter Froggatt 1930s

David Stead

Biologist David Stead was a determined campaigner for the conservation of indigenous Australian biota, and founded the Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia in 1909. He launched an attempt in ca.1930 to restore to NSW the much slaughtered Australian koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), a tree climbing herbivorous marsupial, often referred to, inaccurately, as a bear or the native bear (Ardill 2021). Stead’s restoration ambitions are clearly set out in the historical documentation, but the details of his restoration plan are unknown, although it is quite likely that he aspired to recovery of the koala throughout its natural range in New South Wales.

Although historically interesting, the project did not achieve its goals. Ongoing disputes over methodology and finances arose, and quickly led to the project’s collapse.

Reference:

Peter J Ardill (2021) ‘Innovative Federation and Inter-war Period repair of degraded natural areas and their ecosystems: local government and community restoration of Coast Teatree Leptospermum laevigatum at Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Australia’ The Repair Press Sydney (February) https://ecologicalrestorationhistory.org/articles/

Walter Froggatt

In 1931 distinguished entomologist, Walter Froggatt liaised with North Sydney Council, NSW, and launched a degraded area repair project at Balls Head reserve, Waverton, on Sydney harbour (Ardill 2023). The reserve is located within the traditional homelands of the Cammeraygal First Nations community.

As outlined and planned by Froggatt, the project aspired to the creation of ‘a home for the trees, flowers and birds of old-time Sydney Harbour’ (Ardill 2023: 7). The regional Hawkesbury sandstone flora served as a model for the revegetation work. Today, this form of model is referred to as an ‘indigenous reference ecosystem’ (SERA 2021). A survey of the remnant indigenous vegetation was conducted in 1931, by interested volunteers. Natural regeneration of local tree species was documented. At a series of planting events, locally indigenous tree species were planted.

Unfortunately, Froggatt and North Sydney Council also aspired to the creation of a botanical garden at Balls Head, to display a range of Australian indigenous plant species. Accordingly, throughout the 1930s a number of non-local indigenous species were planted on the site. Quite likely, Froggatt did not understand that introduced (i.e. non-local) indigenous species had potential to degrade ecological functioning on the site, especially if they behaved as environmental weeds (Ardill 2023). Particularly after Froggatt’s death in 1937, the project lapsed into sporadic landscaping efforts.

Froggatt was a member of David Stead’s Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia, and so there is a tantalising but unconfirmed possibility that the two men discussed their respective restoration projects. It is also interesting to note that at the same time that Froggatt was working on his Balls Head repair project, he was also campaigning, unsuccessfully, to prevent the release of cane toads (Bufo marinus) on the Australia mainland, to serve as an insect biological control. Although his opposition was much maligned, Froggatt was correct, and the poisonous toads are now a declared noxious pest in Australia.

References:

Ardill P. J. (2023) “Historical settler understandings of Australian indigenous vegetation

management: Walter Wilson Froggatt and 1930s restoration of locally indigenous vegetation, Balls

Head, Sydney” Repair Press Sydney. https://ecologicalrestorationhistory.org/articles/

SERA (2021) Standards Reference Group ‘National Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration in Australia’ Edition 2.2. Society for Ecological Restoration Australasia www.seraustralasia.com

Acknowledgement:

Image courtesy of the Stanton Library Historical Services, State Library of Victoria and State Library of Queensland.

Arid lands restoration, South Australia, ca.1930

Restoration of degraded arid-zone vegetation communities in Australia appears to have commenced with a series of South Australian projects dating from approximately 1930. Features of contemporary ecological restoration practice are apparent: aspiration to recover high levels of indigenous vegetation complexity, and employment of innovative, quite likely scientifically informed restoration techniques. However, the historical documentation reveals little more about the use of other ecological restoration principles, such as the levels of stakeholder engagement and the implementation of conservation measures.

The new colony of South Australia was formed in 1834, following annexation of First Nations’ homelands. By approximately 1870 a pastoral industry featuring sheep and cattle grazing had been established in the central and north-eastern regions of the colony. Arid-zone climate conditions prevailed: low rainfall averaging approximately 250 millimetres or less per year, and hot summers.

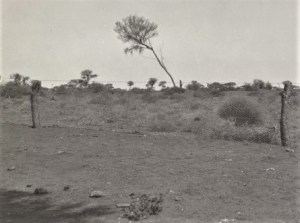

Inappropriate land management practices and exploitative stocking rates were prominent features of the new industry. Widespread degradation of indigenous vegetation soon followed. Stripped of protective plant cover, soils were eroded by regular winds, and massive soil-drifts and bare plains became common (see Gallery).

From approximately 1910, University of Adelaide botanist and plant ecologist, Professor T G Osborn, conducted research into the degradation of the arid-zone indigenous vegetation communities. Concluding that overstocking was the prime cause of vegetation loss, he advised pastoralists to carefully manage stocking levels on their properties. At the university’s Koonamore research centre, Yunta, Osborn demonstrated that key indigenous vegetation species, saltbushes (Atriplex spp.) bluebushes (Maireana spp.) and Mulga (Acacia aneura) had capacity to naturally regenerate (to naturally re-establish), if they were protected from grazing animals (stock exclosure).

From approximately 1930, South Australian pastoralists concerned by vegetation degradation and the resultant wind erosion undertook indigenous vegetation restoration projects on their properties. Although not directly confirmed, it is quite likely that the projects were informed by Osborn’s research. There is also a likelihood that Aboriginal communites living on the stations, which were located on their homelands, shared traditional ecological knowledge with pastoralists, but again, this is not confirmed.

At Wirraminna station, north of Port Augusta, owners George and Dick Jenkins developed fenced ‘flora reserves’. The reserves utilised stock exclosure and natural regeneration concepts to successfully restore indigenous vegetation to soil-drifts (Ardill 2022). The Jenkins brothers appear to have aspired to substantial and possibly even full restoration of indigenous vegetation within each fenced reserve, but little else is known about their revegetation work. Throughout the 1930s flora reserves were developed on other South Australian arid-zone pastoral stations.

South Australian pastoralists also furrowed scalds (areas of eroded, hardened soil), with the intention of facilitating natural regeneration of indigenous vegetation (see Gallery) (Ardill 2022). Encouraged by Koonamore researcher, Terrence Paltridge, Melton station manager, Walter Smith initiated in ca.1930 a particularly successful furrowing project on a wind exposed soil-drift. Moisture and plant seed accumulated in the sheltering furrows, resulting in substantial natural regeneration of indigenous vegetation. Furrowing of soil-drifts and scalds became a widespread South Australian restoration practice during the 1930s.

The success of the South Australian arid-zone revegetation projects was applauded by distinguished Australian scientist, Dr A E V Richardson, an executive member of the national Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), and also by influential Adelaide newspaper editors, and state government administrators and legislators. Desperate to protect the state’s pastoral industry, in 1936 the South Australian government of premier, Richard Butler endorsed stock exclosure, natural regeneration, furrowing and environmentally sensitive stocking practices as effective erosion management and vegetation restoration policies. Financial aid was offered to pastoralists who wished to restore indigenous vegetation to degraded sections of their stations. Additionally, these policies were codified in a new state Soil Conservation Act 1939 (Ardill 2022).

Reference:

Ardill, Peter J (2022) ‘Rekindling memory of environmental repair responses to the Australian wind erosion crisis of 1930–45: ecologically aligned restoration of degraded arid-zone pastoral lands and the resultant shaping of state soil conservation policies’ (January) The Repair Press Sydney. Available at https://ecologicalrestorationhistory.org/articles/

Wirraminna station image courtesy of H Peters Collection, State Library of South Australia.

Restoring the Big Scrub, Lumley Park, Alstonville 1935

The biologically diverse vegetation community, Lowland Rainforest of Subtropical Australia, once flourished for hundreds of kilometres along the coast and hinterlands of southern Queensland and northern New South Wales (OEH 2019). From approximately 1830, timber loggers progressively colonised these regions. The Bundjalung nation of present-day Alstonville and the broader Lismore region, and other regional First Nations communities were forcibly dispossessed of their homelands.

The rainforests were logged for their valuable Red cedar (Toona ciliata), but the remainder of the vegetation survived the logging onslaught. It was a further set of farmer colonists who completely destroyed the subtropical rainforests, to establish dairy and cropping farms. Only scattered remnants of forest, or Big Scrub, as it was locally referred to, had survived by the 1930s.

Alstonville dairy farmer, Ambrose Crawford, was alarmed by the fragile, endangered condition of the scattered, subtropical rainforest remnants. He mustered widespread community support for a rainforest restoration project. Local government entity, Tintenbar Shire Council, approved and financially supported the project.

Work on a two hectares patch of remnant, highly degraded Big Scrub located within Lumley Park, Alstonville, commenced in 1935. Advised by professional botanists and plant ecologists, Crawford selected and replanted plant species that he considered to be typical of the rainforest community, and weeded the exotic climbers and shrubs that infested the site (Lymburner 2018). As well as progressively restoring ecological functioning, Crawford and his small group of restoration colleagues also persevered for decades with the conservation management of the rainforest (McDonald in Jordan III, Lubick 2011). Their legacy is significant, a rare and treasured stand of protected Lowland Subtropical Rainforest.

The successful repair and regeneration of other Big Scrub remnants has been undertaken in more recent times, commencing with Victoria Park Nature Reserve in 1978. These projects have been initiated and undertaken by coalitions of ecologically skilled, conservation minded local residents, regional rainforest advocacy organisation Big Scrub Landcare, government agencies and private landowners (Parkes et al. 2012)

References:

Lymburner S (2018) ‘Lumley Park and rainforest restoration’s early champion. Ambrose Crawford – Regeneration Pioneer. The Lumley Park story.’ (Sydney. Australian Association of Bush Regenerators) Newsletter 137 July. https://www.aabr.org.au/images/stories/resources/newsletters/AABR_News_137.pdf

McDonald T in Jordan III W Lubick G (2011) Making Nature Whole. A History of Ecological Restoration (Washington: Island Press) pp. 71-73

OEH (2019) ‘Lowland Rainforest in the NSW North Coast and Sydney Basin Bioregions – NSW North Coast: Distribution and vegetation associations’ Office of Environment and Heritage NSW Government https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedspeciesapp/profileData.aspx?id=20073&cmaName=NSW+North+Coast

Parkes, T., Delaney, M., Dunphy, M., Woodford, R., Bower, H., Bower, S., Bailey, D., Joseph, R., Nagle, J., Roberts, T., Lymburner, S., with McDonald T. (2012) ‘Big Scrub: A cleared landscape in transition back to forest?’ Ecological Management and Restoration 13:3 (September)

Acknowledgement:

Tweed River image courtesy of the National Library of Australia

Broken Hill regeneration area 1936

Pastoralists commenced seizing the Baaka (Darling River) and extensive plains and low ranges of arid, far western New South Wales (NSW) from approximately 1840. The Barkandji nation and other regional First Nations communities were forcibly dispossessed of their homelands.

The dispossessed Aboriginal communities were confined to government reserves, frequently experiencing harsh conditions and ongoing discrimination (OEH 2021). For many decades, strict state control of individuals and families was imposed by New South Wales state legislation, the Aborigines Protection Act 1909. After a protracted seventeen year administrative and legal process, Barkandji people, including the Wilyakali community of the Broken Hill region, were awarded Native Title rights to their homelands in 2015.

By ca.1900, vast areas of the far western NSW indigenous saltbush (Atriplex spp.) and Mulga (Acacia aneura) vegetation communities had been degraded or even destroyed, predominantly due to pastoral industry overstocking practices. Constant exploitation of timber resources by pastoralists and mining companies, and grazing by exotic fauna species, particularly rabbits and goats, contributed to the destruction of the vegetation. The arid climate featured extended dry periods that impeded vegetation recovery. Vast expanses of the regional landscapes had been largely reduced to barren, eroded wastes by approximately 1900 (Ardill 2023).

Established in the 1880s, western NSW mining centre, Broken Hill, had acquired a population of approximately 30,000 people by the 1930s. Due to the degraded condition of the surrounding countryside and city outskirts, soil-drifts and dust storms regularly afflicted the city’s residents. Mining assayer, resident and conservationist, Albert Morris, was determined to address this issue, by restoring a protective cover of indigenous vegetation to the city’s perimeters.

Morris delighted in and closely studied the biological qualities of the regional ecosystems, and this interest also motivated his restoration aspirations (McDonald in Jordan III, Lubick 2011). He was distressed by the degradation of the beautiful arid landscapes, the widespread loss of indigenous plant communities and the resultant indigenous fauna extinctions. He also perceived the need to reform the environmentally unsustainable pastoral industry (Ardill 2023).

Acquiring considerable expertise as an arid zone botanist, in the 1920s and 1930s Morris studied and trialed various environmental repair techniques. There is a strong possibility that he was influenced by the 1920s restoration research work conducted at Koonamore research centre, South Australia, by University of Adelaide plant ecologist, Professor T G Osborn (see Arid lands restoration, South Australia, ca.1930 on this page). Also, the possibility exists that Morris acquired traditional ecological knowledge from local Aboriginal comunities, but this is unconfirmed.

Confronted by a conservation management vacuum at government level, in 1936 Albert Morris initiated the Broken Hill regeneration area project, an historical Australian degraded area repair project that featured principles of the contemporary natural area restoration practice, ecological restoration. The regeneration area project successfully utilised an innovative stock exclosure technique and natural regeneration concepts to restore a wide range of locally indigenous flora species and high levels of ecological functioning to hundreds of hectares of wasted terrain around western Broken Hill. Use of these restoration techniques reflected Morris’s deep botanical and ecological knowledge. Irrigation and direct planting played only a small role in the project (Ardill 2023).

Residents and government officials were amazed by the dramatic revegetation outcomes. Towering soil-drifts were stablised. From 1939, botanists, ecologists and wind erosion researchers studied the widespread natural regeneration of indigenous plant species that had been fostered by the protective fencing (stock exclosure) of the degraded landscape.

Following Albert Morris’s death in 1939, his wife and conservationist, Margaret Morris, Broken Hill field naturalists and civic administrators campaigned for the completion of the regeneration area, by promoting its impressive botanical and amenity values. The final reserve was fenced in 1958, and the indigenous flora and fauna were formally conserved (see Gallery).

The historical record strongly suggests that opportunities did not arise for Traditional Owners of local homelands, the Wilyakali community, to consider engagement with the regeneration area project. Pearce (2017: 581) acknowledges the achievements of Albert and Margaret Morris and their environmental repair colleagues, but maintains that ‘The Regen portends a trend in ecological restoration to overlook Indigenous people, stories and local knowledge…’

The regeneration area project strongly influenced the New South Wales government’s subsequent development of soil conservation policies and legislation that addressed the severe erosion problems of western New South Wales. In particular, Soil Conservation Service researcher, Noel Beadle, appointed in 1939, was deeply impressed by the revegetation outcomes achieved within the regeneration area, and derived practical erosion management lessons from the project. State legislation passed in 1949 outlawed overstocking and endorsed the use of stock exclosure and natural regeneration programs as effective means of combating erosion in the west (Ardill 2022).

Consisting of a series of fenced regeneration reserves, the regeneration area persists today, supported by Landcare Broken Hill, local field naturalists and the broader community. The beautifully crafted film, ‘Renewal in the desert‘, presents a compelling visual account of the regeneration area project and the contemporary work of local botanists and conservationists.

For an account of Albert Morris’s work in South Australia, see the page, Rehabilitation.

References:

Ardill, Peter J. (2022) ‘Rekindling memory of environmental repair responses to the Australian wind erosion crisis of 1930–45: ecologically aligned restoration of degraded arid-zone pastoral lands and the resultant shaping of state soil conservation policies’ (January) The Repair Press Sydney https://ecologicalrestorationhistory.org/articles/

Ardill, Peter J. (2023) Albert Morris and the Broken Hill regeneration area: ecologically informed

restoration responses to degraded arid landscapes 1936–58 Australian Association of Bush Regenerators Sydney

McDonald, T. in Jordan III W Lubick G (2011) Making Nature Whole. A History of Ecological Restoration (Washington : Island Press) pp. 73-75

OEH (2021) ‘Bioregions of NSW/A Brief overview of NSW/NSW-Regional History/New South Wales- Aboriginal occupation-Aboriginal occupation of the Western Division’ New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage. Sydney. NSW Department Planning Industry Environment https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-/media/OEH/Corporate-Site/Documents/Animals-and-plants/Bioregions/bioregions-of-new-south-wales.pdf

Pearce, L. M. (2017) ‘Restoring Broken Histories’ Australian Historical Studies 48:4 569-591

Acknowledgements:

Outback Archives, Broken Hill Library, houses the archives of the Barrier Field Naturalists Club, and other relevant archives.

Cable Hill image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

Film link ‘Renewal in the desert’ courtesy Australian Association of Bush Regenerators (AABR) 2021. Director: Virginia Bear, Little Gecko Media. Script: Virginia Bear, Tein McDonald.

Australian Alps ca.1960

The traditional lands of the Ngarigo and Walgal (or Wolgalu) nations embraced the high country alps and Monaro plains of south-east Australia. Settlers commenced seizing these lands in the 1820s, dispossessing the Ngarigo and Walgal communities and rapidly disrupting their traditional cultural and land management practices. Introduced diseases devastated communities (Environment 2016).

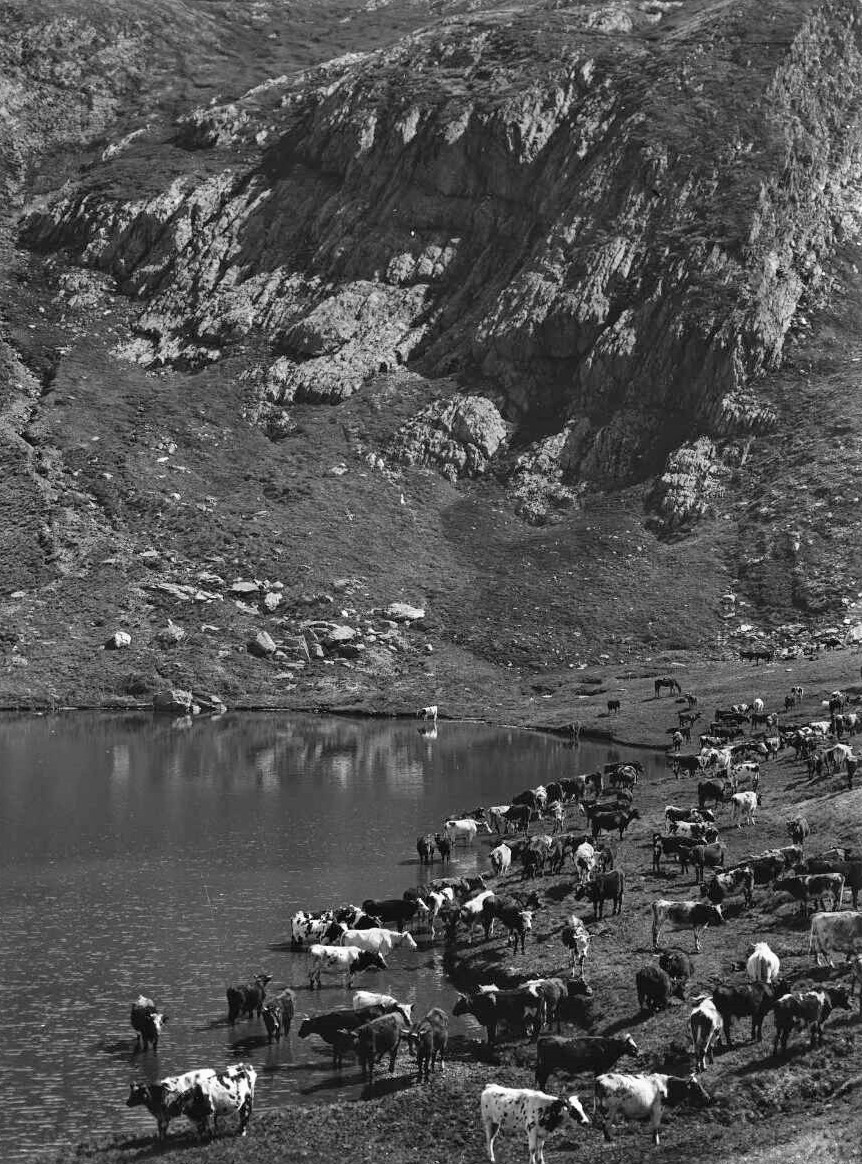

Over succeeding decades, the livestock rearing and burning activities of the settlers, or pastoralists as they were also referred to, significantly degraded the indigenous vegetation of the alpine high country. The resulting severe erosion destroyed many of the alpine bog and fen ecosystems.

The film ‘Snowy Hydro – Conservation in the Snowy Mountains’ vividly illustrates the erosion problems that had developed in the Australian Alps by 1950 (Malcolm 1955). See https://aso.gov.au/titles/sponsored-films/snowy-hydro-conservation-snowy/clip1/# . As the film reveals, by the mid 1950s attempts were being made by government agencies to remediate eroded alpine areas. Although innovative, they unfortunately involved the use of introduced plant species, and not locally indigenous species.

The worsening erosion led to substantial flows of soil, gravel and rock into the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority’s reservoirs, and concerns arose that water storage capacity would be seriously compromised. Funded by the Authority, a fresh series of erosion management projects commenced in approximately 1960.

The initial project was managed by ecologist, Roger Good and the New South Wales Soil Conservation Service. Officially, the project was undertaken for utilitarian reasons, but Good aspired to the progressive recovery of biodiversity, and restoration of local alpine flora was a major priority (Good, Johnston 2019). Botanical surveys and plant propagation research were undertaken by Good’s restoration colleagues, the botanists and plant ecologists, Alec Costin and Dane Wimbush. They significantly contributed to the design of the restoration projects (Good, Johnston 2019; Good McDonald 2016) .

Natural regeneration was fostered, and where necessary indigenous flora was planted. With vegetation and soil stability reinstated, flows of sediments into the reservoirs dramatically decreased.

Management of the erosion control projects passed to the newly formed New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service in the 1970s. Good’s extensive ecological knowledge and environmental repair skills were retained, and he also managed post 2003 alpine bushfire recovery projects.

As well as being historically important, the Australian Alps restoration projects are notable for the substantial input provided by scientists. Several strands of Australian scientific expertise developed throughout the course of the restoration projects, involving alpine botany, alpine ecology and restoration ecology (Good, McDonald 2016). Restoration ecology is a relatively new science, developed to inform ecological restoration practitioners and their need for precise, often previously unresearched scientific information. See Ecological restoration

Today, members of the Monaro Ngarigo community work with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service to manage the Kosciuszko National Park, which extends across the Australian Alps (ABC 2016). Introduced species, particularly feral horses, continue to threaten the indigenous biological diversity of the park and alps.

References:

ABC (2016) ‘Snowy Mountains Aboriginal people to be formally involved in managing Kosciuszko National Park’ Australian Broadcasting Commission https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-06-26/ngarigo-people-to-be-formally-involved-in-managing-kosciuszko/7543734

Environment (2016) ‘ Australian Alps – regional history – Aboriginal occupation’ Australian Alps Bioregion NSW Department Planning, Industry, Environment April https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/bioregions/AustralianAlps-RegionalHistory.htm

Good, R., Johnston, S. (2019) ‘Rehabilitation and revegetation of the Kosciuszko summit area, following the removal of grazing – An historic review’ Ecological Management and Restoration 20:1 January

Good, R., McDonald, T. (2016) ‘Alpine restoration in the NSW Snowy Mountains: Interview with Roger Good’ Ecological Management and Restoration 17:1 January

Malcolm, H. (1955) Film: “Snowy Hydro – Conservation in the Snowy Mountains’ Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority https://aso.gov.au/titles/sponsored-films/snowy-hydro-conservation-snowy/clip1/#

Acknowledgements:

Snowy Mountains image courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales

Alpine herbfield image courtesy CSIRO ScienceImage

Tower Hill, Victoria 1961

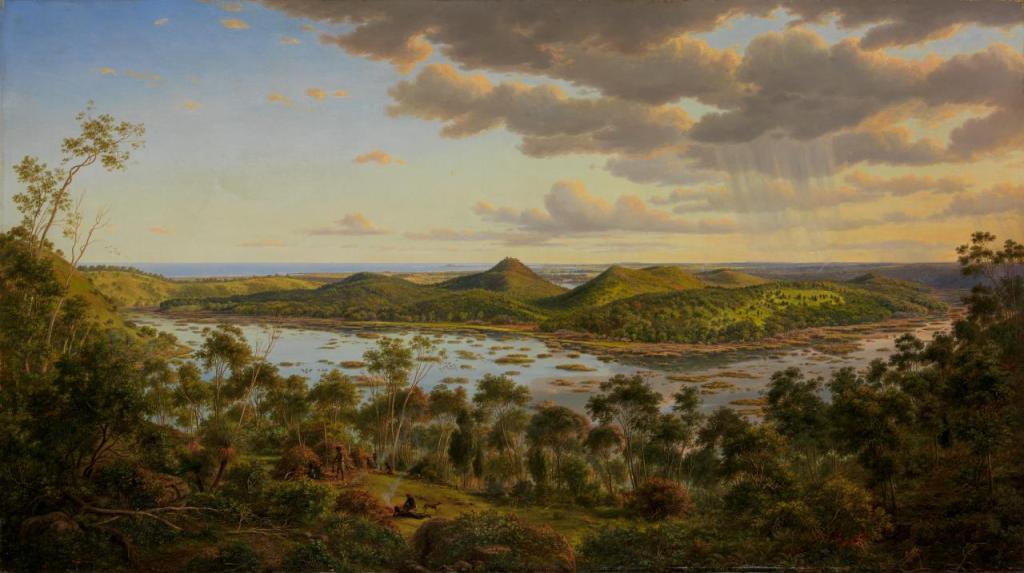

Tower Hill, located near Warrnambool, western Victoria, is a place of great cultural significance and value for regional Traditional Owners and Custodians, the Eastern Maar nation.

At Tower Hill reserve, a state government funded project pursued recovery of indigenous flora and fauna on the highly degraded site. The environmental ideals of USA ecologist and environmental ethicist, Aldo Leopold, influenced the project (Bonyhady 2000). Leopold was active in the historically significant 1935 University of Wisconsin Arboretum ecosystem reconstruction project (Jordan III, Lubick 2011).

The Tower Hill project appears to have aspired to the reinstatement of substantial to full ecological functioning within the reserve. A group of Warrnambool field naturalists and Victorian Government Fisheries and Wildlife Branch officers commenced replanting in 1961. Pre-degradation era vegetation communities were investigated, plants were propagated from locally collected seed, additional botanical advice came from Melbourne’s National Herbarium and re-introduction of indigenous fauna was attempted (Bonyhady 2000). Two nineteenth-century items, a landscape painting and a travel guide book, provided additional information about the original condition of the restoration site (Bonyhady 2000). Today, these restoration efforts are celebrated and conserved as Tower Hill Wildlife Reserve.

Reference:

Bonyhady T (2000) The Colonial Earth (Melbourne University Press : Melbourne) pp.340-366

Jordan III, W. Lubick, G. Making Nature Whole. A History of Ecological Restoration (Island Press : Washington 2011)

Acknowledgement:

Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria

Bushland restoration and the Bradley Method, Sydney ca.1960

Sisters Joan and Eileen Bradley played signficant, innovative roles during the pioneering early days of the Sydney bush regeneration movement. Their Bradley Method has informed many historical and contemporary Australian natural area restoration projects.

From approximately 1960, Joan and Eileen developed a keen interest in the management of the introduced flora species, or environmental weeds, that were threatening the quality of their local bushland at Mosman, Sydney. They devised a weed and degraded area treatment technique that became known as the Bradley Method (Radi 1993). Their technique, meticulously applied, made use of indigenous flora species’ natural resilience: the evolved capacity to recover from disturbance and degrading impacts by naturally regenerating (Bradley 1971; May 1996).

Joan and Eileen Bradley promoted their work and sparked wider interest in the restoration of Sydney’s many degraded bushland ecosystems. The New South Wales National Trust took up the Bradleys’ ideas in the 1970s (May 1996). The Trust became involved with professional bush regeneration contract work, and was providing contracted restoration services to nine Sydney local government councils by 1983 (Buchanan 2007). In 1980, the Trust commenced offering bush regeneration training courses to professional bush regenerators and volunteer bushcarers (Buchanan 2007).

From ca.1980, an increasing number of Sydney’s local government councils commenced employing professional bush regenerators to manage local bushland that had been degraded by environmental weeds (Gye, McDonald 2019). Subsequently, councils additionally employed professional bushcare officers to guide the work of bushcare groups and their volunteer bushcarers. The Bradley Method inspired the development of effective weed management strategies on many of these Sydney bushland restoration sites.

However, a 1980s attempt to modify the Bradley Method and adapt it for use on a rainforest restoration project located at Wingham, on the north coast of New South Wales, encountered strong opposition from the Method’s more strict adherents in Sydney. Nevertheless, it was the adapted regional approach that proved to be successful (Buchanan 2007; Franklin 2015; Little Gecko Media 2024). For full details of this story, See the entry Wingham Brush 1980 below.

Indeed, and as illustrated by the Lumley Park (Crawford 1935), Broken Hill (Morris 1936), Australian Alps (Good 1960s) and Mosman (Bradleys 1960s) projects, the early development of restoration in settler Australia was characterised by the development of restoration techniques that reflected the severity of site degradation, and local ecological conditions. The historical evidence reveals that ideologically fixated, inflexible restoration approaches that insist on strict adherence to a rigid set of principles represent a retrograde, aberrant approach to Australian restoration practice. In fact, Joan Bradley supported adaptation of her Method to the environmental and degradation realities of each site (Little Gecko Media 2024). As practice has expanded in Australia, a range of ecologically appropriate, degraded area management techniques have been developed (Buchanan 2007). Today, the Bradley Method is regarded as an effective restoration technique that is adaptable to local environmental conditions and restoration challenges.

References:

Bradley, J. (1971) Bush Regeneration (Sydney : Mosman Parklands and Ashton Park Association)

Buchanan, R. (2007) “How it all began – Robin Buchanan’s story of bush regeneration’s early days” AABR News 96 (February) Australian Association of Bush Regenerators https://www.aabr.org.au/learn/publications-presentations/aabr-newsletters/

Franklin, N. (2015) ‘The other green army: a history of bush regeneration’ Parts One and Two Earshot Australian Broadcasting Commission https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/earshot/the-other-green-army-a-history-of-bush-regeneration/6364500

Gye, J., McDonald, T. (2019) ‘Order of Australia Award for Dr Tein McDonald’ AABR News 141 (July) Australian Association of Bush Regenerators

May, T. (1996) ‘Bringing Back The Bush’ Australian Plants Online Australian Society For Growing Native Plants http://anpsa.org.au/APOL4/dec96-5.html

Radi, H. (1993) ‘Bradley, Joan Burton (1916–1982)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bradley-joan-burton-10001/text16853

Wingham Brush 1980

Dispossession of the Biripi (or Birpai) People, Traditional Owners of Manning River homelands on the mid-north coast of NSW, commenced ca.1830. The Biripi resisted; punitive expeditions were undertaken by settlers, and massacres of the Manning River communities were perpetrated (Ramsland 2001). Colonising farmers seized the rich alluvial plains of the river and introduced often inappropriate European modes of agriculture. The biodiverse Lowland Subtropical Rainforest of the region was cleared, and rapidly reduced to scattered remnants by the early decades of the twentieth century.

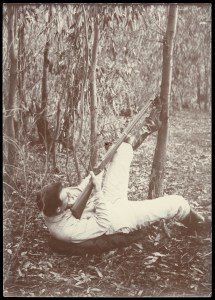

A nine hectares rainforest remnant that did fortunately survive settler clearing was located on the outskirts of Wingham township, on the Manning River. The remnant became known as Wingham Brush. Plant species introduced to Australia had established a firm foothold throughout the Brush by the 1920s, particularly climbing vines (see illustration below). In 1980 local bush regenerator, John Stockard, fellow workers and the New South Wales National Trust commenced a lengthy, arduous and highly successful project to restore the Brush, ‘to keep the ecological processes going’ (Stockard, Pallin undated).

Stockard soon realised that the Bradley Method and its intricate weeding techniques would not prove to be totally adequate restoration responses, as the level of degradation within the Brush was so high. Innovative repair techniques more appropriate to the site would have to be devised, in order to successfully manage the variety of exotic plant species, particularly the vines that had enveloped much of the rainforest canopy (Stockard 1996).

Stockard adapted the Bradley Method to the realities of the highly degraded site (Buchanan 2007; Franklin 2015; Little Gecko Media 2024). The introduction of herbicides, and the development of efficient and effective means of applying them, were important innovations (Little Gecko Media 2024). Joan Bradley supported Stockard and his restoration methods, and visited the Brush at least once (Little Gecko Media 2024).

Following Joan’s death in 1982, dogmatic Sydney based adherents of the Bradley Method fiercely opposed Stockard’s innovations. This led to the 1984 “Battle of the Brush”, and unfortunately, Stockard was dismissed from the project.

However, ultimately Stockard’s adaptation of the Bradley Method proved to be highly successful (Harden et al. 2004). A National Herbarium of NSW report praised his work and the resultant site outcomes (Little Gecko Media 2024).

Now fully restored, Wingham Brush thrives as a healthy rainforest ecosystem (Little Gecko Media 2024). As at ca.2020, the dedicated Stockard and his restoration colleagues continue to conduct maintenance work in the reserve, now known as the Wingham Brush Nature Reserve (Brodie 2018). The rainforest that grows in the reserve has been listed as a critically endangered ecological community by the Australian government. As is the case with many restored conservation sites, the Brush and its indigenous flora and fauna still face ongoing degrading impacts from weeds, climate change, dogs, cats and damaging human behaviour. See https://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/-/media/visitor/files/pdf/brochures/wingham-brush-pdf.pdf .

References:

Buchanan, R. (2007) “How it all began – Robin Buchanan’s story of bush regeneration’s early days” AABR Newsletter 96 (February) Australian Association of Bush Regenerators https://www.aabr.org.au/learn/publications-presentations/aabr-newsletters/

Brodie, L. (2018) ‘AABR Visit to Wingham Brush’ Australian Association of Bush Regenerators Newsletter 138 October Australian Association of Bush Regenerators https://www.aabr.org.au/images/stories/resources/newsletters/AABR_News_138.pdf

Franklin, N. (2015) ‘The other green army: a history of bush regeneration’ Parts One and Two Earshot Australian Broadcasting Commission https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/earshot/the-other-green-army-a-history-of-bush-regeneration/6364500

Harden, G. J., Fox, M.D., Fox, B. J. (2004) ‘Monitoring and assessment of restoration of a rainforest remnant at Wingham Brush, NSW’ Austral Ecology 29, 489–507

Little Gecko Media (2024) Film: ‘Rescuing Wingham Brush’ Little Gecko Media for Australian Association of Bush Regenerators Sydney

Ramsland, J. (2001) Custodians of the Soil (Greater Taree Council: Taree)

Stockard, J., Pallin, N. (undated) ‘The regeneration Of Wingham Brush NSW’ Australian Association of Bush Regenerators https://www.aabr.org.au/the-regeneration-of-wingham-brush-nsw/

Stockard, J. D. (1996) ‘Restoration of Wingham Brush 1980-1996’ Eleventh Australian Weeds Conference Proceedings Council of Australasian Weeds Societies Inc. Weed Science Society of Victoria Inc. (30 September – 3 October)

Acknowledgement:

Wingham Brush 1937 image courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales

——-

Page updated January 2025

Copyright © Peter J Ardill 2021