Introduction

Environmentally degrading behaviour was a hallmark of nineteenth-century settler interactions with the Australian continent and its varied ecosystems and landscapes. These behaviours included poor management and outright exploitation of natural resources, widespread employment of European land use practices totally unsuited to local climatic, soil and vegetation conditions, and the introduction of exotic flora and fauna species that adversely impacted upon indigenous biota and abiota. As a result, many natural ecosystems, including subtropical rainforests, temperate grasslands and rangelands were severely degraded, or even totally destroyed (Lines 1991; Barr, Cary 1992; Bonyhady 2000; Muir 2014; Frost 2020).

Confronted with the social, economic and environmental consequences of natural area degradation, some colonial administrators, naturalists, conservationists, community groups and individuals did attempt to manage natural resources in a more sustainable manner, by regulating degrading environmental behaviour and adapting land use techniques to prevailing environmental conditions (Barr, Cary 1992; Bonyhady 2000; Hutton, Connors 1999; Mosley 2012). This page, Managing Impacts, presents significant historical examples of Australian settler environmental conservation management.

References:

Barr N, Cary J (1992) Greening A Brown Land (Melbourne: MacMillan Education)

Bonyhady T (2000) The Colonial Earth (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press)

Frost, W. (2020) An Environmental History of Australian Rainforests until 1939 (Routledge)

Hutton D., Connors L. (1999) A History of the Australian Environment Movement

Cambridge. (Cambridge University Press)

Lines W (1991) Taming the Great South Land (Georgia: University Georgia Press)

Mosley G. (2012) The First National Park: A Natural for World Heritage Envirobook

Sutherland Shire Environment Centre Sydney https://www.ssec.org.au/firstnationalpark/First%20National%20Park.pdf

Muir, C. (2014) The Broken promise of Agricultural Progress: An Environmental History (Routledge)

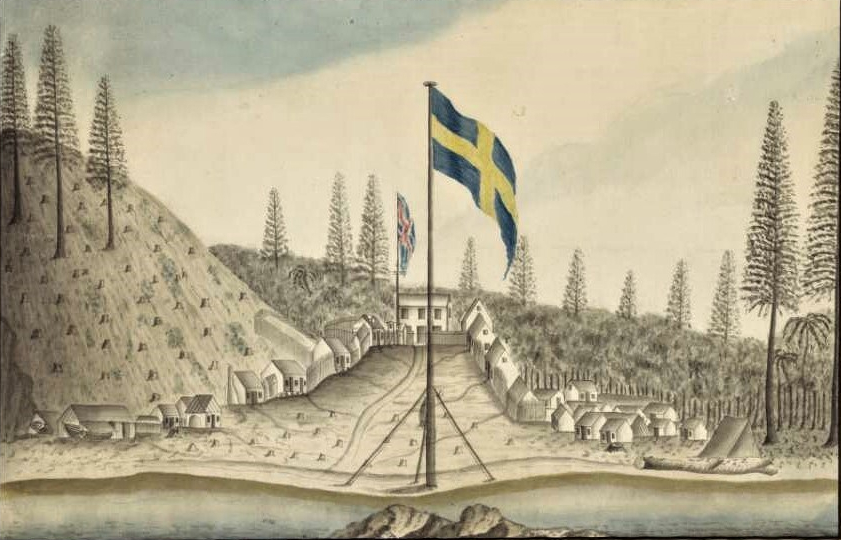

Conserving the Mount Pitt Bird, Norfolk Island ca.1790

Following colonisation of Sydney in 1788, a small British settlement was established on Norfolk Island, also in 1788. The island is located 1700 kilometres to the north-east of Sydney. Crops failed and supplies ran short in 1790. To avoid starvation, the convicts, military personnel and free settlers on the island commenced hunting and eating the Mount Pitt Bird (or Providence Petrel) Pterodroma solandri, a petrel. The birds were hunted ruthlessly when they flocked to the island for their annual breeding event (Bonyhady 2000).

Norfolk Island’s British commander, Governor Ross, attempted to conserve the birds. He placed daily limits on the quantities that could be killed by each person, and tried to protect the petrel’s habitat by regulating forestry practices. Ross’s actions were largely motivated by the need to secure ongoing ecosystem services, in the form of food, but humanitarian concerns were also expressed by some of the island’s colonists (Bonyhady 2000).

Despite Governor Ross’s regulatory measures, up to a million birds had been killed by 1795. The Mount Pitt Bird was reduced to a condition of local extinction, and the petrel no longer breeds on Norfolk Island.

Reference:

Bonyhady T (2000) The Colonial Earth (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press)

Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia (NLA)

Nineteenth-century colonial management of introduced flora species and their degrading impacts

Australian colonial settlers predominantly utilised European modes of settlement and agriculture. A variety of flora and fauna species were introduced to the continent (Barr, Cary 1992).

Presented with favourable environmental circumstances, an introduced flora species (an exotic) can reproduce and spread so vigorously that local vegetation communities are overwhelmed. Scotch Broom Cytisus scoparius was thriving ‘luxuriantly’ in the mild climate of Tasmania by the 1820s, and was regarded as a ‘very elegant ornaments to the gardens’ (Anon ‘State of the Weather’ Hobart Town Gazette 21 October 1826). Broom is now a declared noxious species throughout much of Australia, as its dense growth habit smothers landscapes and suppresses many indigenous plant species.

By the 1840s serious concern about the economic and environmental impacts of many introduced species had developed, as they spread throughout areas of commercially productive land. Scotch thistle degrades the fleece of sheep, and had expanded into the Victorian countryside by ca.1850. The capacity of this ‘noxious plant’ to leave a region ‘a wilderness, a waste and a desert’ aroused considerable alarm (Anon ‘Devil’s River’ Geelong Advertiser 9 August 1849 p.1). Bathurst burr, a South American species, was introduced to Australia in approximately the 1840s, and had become ‘an evil of serious magnitude’ in central New South Wales by ca.1850 (Anon ‘The Bathurst Burr’ Bathurst Free Press 4 May 1850 p.4).

The various colonial legislatures attempted to manage the spread and impact of the most damaging introduced flora species. ‘An Act to make provision for the eradication of certain Thistle Plants and the Bathurst Burr’ was assented to by the Victorian parliament in 1856, and other Australian colonies quickly introduced similar legislation. The Victorian legislation provided for the mandatory treatment of thistle and burr by private landowners.

Prickly-pear, a form of cactus, was first reported in Australia during the 1830s, and in the latter decades of the nineteenth century spread rapidly throughout eastern Australia. The New South Wales legislature passed the Prickly-pear Destruction Act in 1886. The legislation vested authority in state appointed inspectors to mandate the eradication of prickly-pear on both Crown and private land. This attempt at manual control failed, and prickly-pear had developed into a major Australian agricultural and environmental weed by the early twentieth century.

Following the First World War (1914-1918), the newly formed Commonwealth Prickly Pear Board searched for a scientifically vetted biological control that could be imported to control the cactus. A moth, Cactoblastis cactorum (South America) and the cochineal bug Dactylopius opuntiae (Central America) both proved to be effective consumers of the cactus, and it was effectively controlled by the 1930s (Invasive Species Council 2021).

Much of the interest displayed by colonial administrators, legislators and farmers in managing unwanted, weedy introduced flora species revolved around the need to limit the adverse social and economic impacts that these species created. However, some colonists also valued Australian flora and fauna for their uniqueness, special biological qualities and beauty. An historically significant attempt to manage an introduced flora species and the threat that it posed to an intrinsically valued Australian flora species took place in 1894 at Susan Island, Grafton, and is reported on this page.

References:

Barr N, Cary J (1992) Greening A Brown Land (Melbourne : MacMillan Education)

Invasive Species Council (2021) ‘Threats to Nature Taming A Cactus’ Case Studies Invasive Species Council https://invasives.org.au/publications/case-study-taming-a-cactus/

Images courtesy of the National Library of Australia and the State Library of Queensland

Conservation management of degrading impacts, Beaumaris, Port Phillip Bay 1890

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the state level of government was a key player in Australian settler environmental conservation management. However, local government was progressively established throughout the colonies from the 1870s, and this lower tier of government has also played a significant role in environmental management (Ardill 2021).

What appears to have been an early example of local government engagement with conservation management occurred in 1890 at Beaumaris, a small village located on the eastern foreshores of Nairm (Port Phillip Bay), Melbourne, Victoria. Mr Bryan Moore was concerned about the fate of the foreshore’s indigenous flora species. He obtained the administrative and financial support of Moorabbin Shire Council and conducted an ‘experiment’, designed to

preserve the ti-tree, acacia, the native cherry, and the honeysuckle and other shrubs …The idea has become general that this native vegetation ought to be preserved, but those of this mind have not gone further than to leave the scrub alone…a policy of masterly inactivity is not sufficient… for the sea coast near Melbourne… (Ardill 2021 p.17).

Mr Moore anticipated that the creation of access pathways to the beach, and the provision of dedicated scenic and picnicking areas would remove the need for beach-goers to clear and trample the foreshore’s natural vegetation. The success or otherwise of his conservation management experiment was not recorded, but as the foreshore reserves and their beaches were extremely popular recreation venues, it is possible that the degrading impacts continued. By 1896, council staff were replanting Coast Tea-tree in the foreshore reserves, and the council had appointed a ranger to patrol the foreshores in the school holidays, in an attempt to minimise damage to the vegetation (Ardill 2021).

Moore’s attempt to engage in proactive management and conserve indigenous vegetation was quite progressive. Concerted interest in the managment and conservation of Australia’s natural environments was only just developing in the late nineteenth century; arguably, a conservation movement was developing at this time (Hutton, Connors 1999). In fact, the foreshore reserves of Port Phillip Bay and their indigenous flora had been subjected to unregulated, degrading impacts for decades. Moore’s conservation management ‘experiment’ preceded by four years the gazettal in 1894 of what was quite possibly Australia’s first dedicated indigenous flora and fauna conservation area, Ku-ring-gai Chase reserve, Sydney (Mosley 2012).

References:

Ardill,P. J. (2021) ‘Innovative Federation and Inter-war Period repair of degraded natural areas and their ecosystems: local government and community restoration of Coast Teatree Leptospermum laevigatum at Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Australia’ The Repair Press Sydney (February) https://ecologicalrestorationhistory.org/articles/

Hutton, D., Connors, L. (1999) A History of the Australian Environment Movement (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press)

Mosley, G. (2012) The First National Park: A Natural for World Heritage (Sutherland Shire Environment Centre & Envirobook : Sydney) https://www.ssec.org.au/firstnationalpark/First%20National%20Park.pdf

Images courtesy of the State Library of Victoria (SLVIC) and State Library of South Australia (SLSA)

Historical management of introduced flora species threatening admired indigenous flora, Susan Island, Grafton 1894

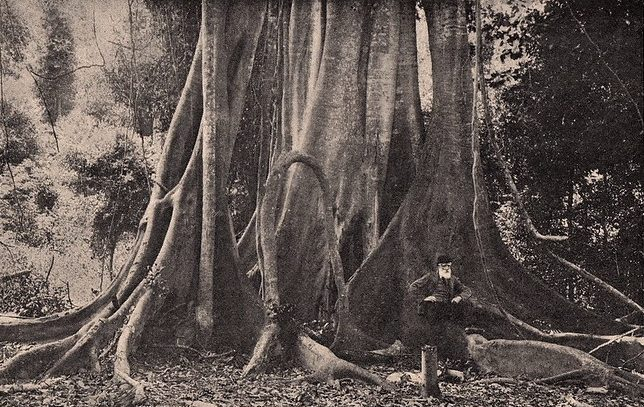

The extensive Clarence River catchment, located on the north-east coast of New South Wales approximately 700 kilometres north of Sydney, is home to Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl First Nation communities. Forced dispossession of the Traditional Owners by timber cutters commenced in the 1840s. Selective, exhaustive logging of the commercially valuable rainforest tree, Red Cedar Toona ciliata was undertaken. Known today as Lowland Rainforest on Floodplain, the remainder of the Clarence River rainforest community was progressively burnt and cleared for farming.

Susan Island is a well vegetated, mobile shoal located in the middle of the Clarence River, adjacent to Grafton township. The Red cedar on the island had been logged by approximately 1850, but the remainder of the rainforest that covered the island had not been cleared for agriculture, and in 1870 was still in a relatively intact condition. For reasons unknown, the island was declared a recreation reserve in 1870. The trustees of the reserve admired and valued the rich biological and aesthetic qualities of the rainforest and attempted to preserve these qualities, despite public pressure to clear the vegetation and develop the island as a health and recreation resort (Ardill 2019).

The introduced plant species, lantana Lantana camara had become established on Susan Island by ca.1890, quite possibly in a small cleared area. Recognising the threat that the lantana posed to the integrity of the adjacent rainforest community, the trustees arranged for slashing work to be undertaken in 1894. Skilled naturalist and reserve trustee, James Clarence Wilcox initiated further weed management works in ca.1900. These efforts appear to have been largely ineffectual, and the lantana, additional weed species, vegetation clearing and stock grazing had substantially devastated the mid-section of the island by the 1920s.

The 1894 attempt by the trustees to manage the lantana is the earliest known work undertaken by Australian settlers to control an introduced flora species that was threatening intrinsically valued indigenous flora and avifauna. Despite the failure of the weeding work, a section of undegraded, resilient rainforest resisted the lantana onslaught, and survived. Today, Susan Island nature reserve is managed by the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, with valued input coming from the Traditional Custodian Nyami Julgaa womens’ group and the regional community.

Reference:

Ardill, P. J. (2019) ‘Colonial and twentieth-century management of exotic species threatening intrinsically valued indigenous flora: Susan Island, Lumley Park, Broken Hill’, Australasian Plant Conservation 28:2 (September – November)

Images courtesy of the National Library of Australia and State Library of Victoria

Professional management of an exotic flora species threatening valued indigenous flora, Hampton, Port Phillip Bay ca.1930

Flora species introduced from overseas (exotics) have frequently acquired environmental weed status in Australia, and indigenous Australian flora species introduced to areas outside their natural range can also develop into environmental weeds, both nationally and internationally (Groves 2001). Environmental weeds can overwhelm locally evolved plant communities, often displacing indigenous animals in the process.

What may have been Australia’s first exercise in the control of an environmental weed by a professional vegetation management company took place at Hampton, Nairm (Port Phillip Bay), Melbourne, in approximately 1934. Pampas Lily of the Valley was introduced to Australia from South America, and became a popular ornamental plant. But at Sandringham Shire Council the lily was causing “councillors considerable anxiety, and it was feared that it would destroy the foreshore native flora”, including the “ti-tree and other native flora” (Anon ‘Destructive Noxious Weed’ Age 12 July 1934 p.12).

To eradicate the lily, in approximately 1934 the council initiated weeding programs at unspecified foreshore reserves in Hampton. However, members of the public complained that “unskilled workers were destroying much native flora”, in their attempts to control the lily (Anon ‘Pampas Lily of the Valley’ Age 10 January 1935). Responding, the council employed a specialist weeding company, which eventually claimed to have successfully eliminated the lily from the reserves. Council curator, Mr Rumble was charged with the task of monitoring for any signs of regrowth (Anon ‘Native Flora Threatened’ Argus 22 June 1935).

The historical evidence suggests that the company engaged in weed management practices that characterise the contemporary environmental repair practice, “bush regeneration”, as it displayed an intention to remove the environmental weed while also carefully conserving valued indigenous plants.

Reference:

Groves, R. H. (2001) “Can Australian native plants be weeds?” Proceedings of a seminar held at Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 22 February 2001. Weed Science Society of Victoria Inc. Plant Protection Quarterly Vol.16(3) 2001

https://caws.org.nz/PPQ1617/PPQ%2016-3%20pp114-117%20Groves.pdf

Image courtesy of the State Library of Victoria (SLVIC)

———