Introduction — rehabilitation

On some degraded sites, recovery of substantial to full ecological functioning cannot be achieved, or is not practicable. For example, it may be the case that substantial recovery of characteristic indigenous fauna species cannot be undertaken, due to residential or commercial constraints e.g. within an urban park. These types of projects, characterised as rehabilitation, aspire to recovery of more modest levels of ecological functioning.

Rehabilitation is the process of reinstating a level of ecosystem functionality (but not substantial native biota) on degraded sites where ecological restoration is not the aspiration, as a means of enabling ongoing provision of ecosystem goods and services (SERA 2021: 31).

The earliest known rehabilitation projects undertaken by Australian settlers commenced in late nineteenth-century, colonial Melbourne. Working together, volunteer community members and local government played prominent roles.

Reference:

SERA (2021) Standards Reference Group ‘National Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration in Australia’ Edition 2.2. Society for Ecological Restoration Australasia www.seraustralasia.com

Port Phillip Bay 1896

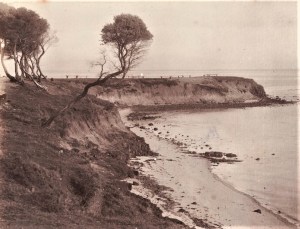

An historically significant series of Australian settler, degraded area repair projects that focused on the reinstatement of natural qualities linked to amenity and commercial values took place along the east coast of Nairm (or Port Phillip Bay), Melbourne, Victoria, between 1896 and the 1930s (Ardill 2021). The projects were conducted on the traditional homelands of Boon wurrung language group communities of the Eastern Kulin nation. Dispossession of these communities commenced with the European invasion of Nairm in 1835. Introduced diseases took a heavy toll on the Eastern Kulin population; settler aggression and social ostracism followed.

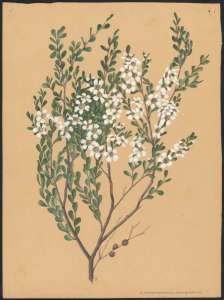

The Eastern Kulin communities had carefully managed their homelands, including the east coast foreshores of Nairm. However, following settler occupation and expansion, the foreshore indigenous vegetation communities were progressively degraded. In particular, small to medium sized tree and key species Coast Teatree Gaudium laevigatum (syn. Leptospermum laevigatum) was extensively logged for firewood. Regenerating seedlings were destroyed by livestock and campers.

The Port Phillip Bay rehabilitation projects involved the replanting of Coast Teatree in foreshore reserves located at Brighton, Hampton, Sandringham, Black Rock, Beaumaris and Mornington (see Gallery). Concern at the degradation and loss of amenity qualities enjoyed by local residents and tourists, in the form of shelter and beauty, strongly motivated participation by individuals and community groups. However, alarm at diminishing levels of cherished biological qualities, and recognition of the need to reinstate and conserve these qualities, also informed some participants.

Local government played a prominent role in many of the projects. Brighton Council initiated and managed the first attempts at replanting Coast Teatree, in 1896. Considered a highly experimental undertaking at the time, councillors and staff were delighted with the outcomes. Mordialloc, Sandringham and Mornington Councils also managed and financially supported replanting of Coast Teatree.

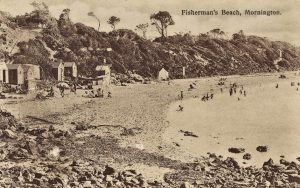

Strong community engagement was a prominent feature of the Port Phillip Bay projects. In 1903, members of the Mornington Progress Association, with the support of Mornington Shire Council, undertook a series of replanting sessions involving thousands of Coast Teatrees, extending south to Fishermans Beach.

The success of the Mornington replanting efforts is likely to have encouraged further community engagement with replanting projects along the Port Phillip Bay foreshores. The Hampton Progress Association undertook an ambitious Coast Teatree replanting project within foreshore reserves in 1911, at the considerable cost of seventy pounds, and the Black Rock Progress Association replanted Coast Teatree at Half Moon Bay in 1913.

Sandringham Council, local residents and Beaumaris Improvement League joined forces to stage an innovative repair project at Beaumaris. This project was ongoing: the Coast Teatree replanting sessions were conducted on successive weekends during the winter months, from 1924 until 1927. The council supplied tools and plants. Children participated. Historical reports of of the project suggest that the residents were engaging in a form of environmental stewardship.

Unfortunately, it would appear that the Port Phillip Bay rehabilitation efforts petered out in the 1930s and 1940s. Today, only scattered remnants of the original rehabilitation work remain. Various Port Phillip Bay local government authorities and community groups continue to maintain the remaining patches of indigenous vegetation along the foreshores, and work to foster the recovery of degraded areas. Members of the Eastern Kulin nation continue to maintain physical and spiritual links with their traditional lands.

Reference:

Ardill, Peter J. (2021) ‘Innovative Federation and Inter-war Period repair of degraded natural areas and their ecosystems: local government and community restoration of Coast Teatree Leptospermum laevigatum at Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Australia’ The Repair Press Sydney (February) https://ecologicalrestorationhistory.org/articles/

Images courtesy of the National Library of Australia (NLA) and State Library of Victoria (SLVIC)

Whyalla 1930s

Historically significant Australian settler rehabilitation projects commenced on the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia, between 1935 and 1937 (the precise date is unknown). The projects were conducted on the traditional homelands of the dispossessed Barngarla People (also known as Parnkalla or Pangkala). Barngarla communities were awarded native title rights to expanses of the Eyre Peninsula in 2015.

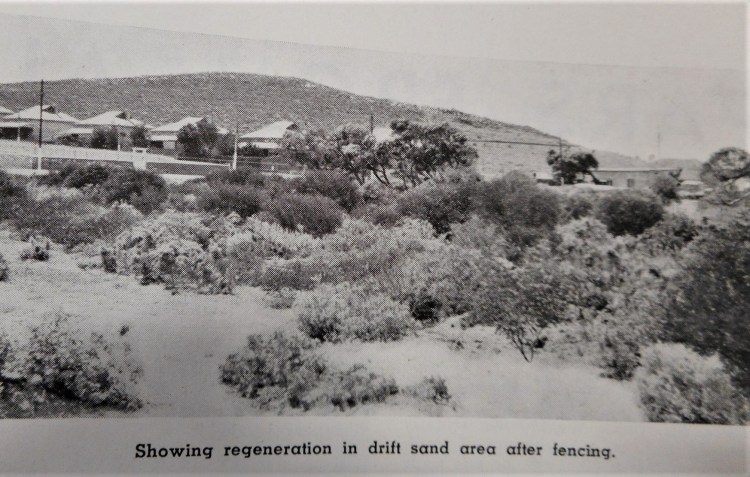

At the invitation of prominent industrialist, Essington Lewis and his Broken Hill Proprietary Company, botanist and conservationist, Albert Morris (see the page Ecological Restoration) developed two natural regeneration projects at Whyalla, a small but important industrial township. The projects were located at Whyalla beach and Hummock Hill, and targeted the restoration of degraded indigenous vegetation. It is likely that herds of dairy cattle had progressively degraded the two sites.

For Lewis and his company, the achievement of amenity focused dust and sand control were important objectives. A conservationist, Morris quite possibly aspired to substantial and even full restoration of the indigenous vegetation, aspirations characteristic of ecological restoration (see Gallery). However, very little formal documentation of the projects exists, and precise details about how and when they were implemented and how the restored sites were subsequently managed are not available.

Morris correctly anticipated that the indigenous flora would naturally regenerate if the two sites were protectively fenced to exclude grazing stock (known as stock exclosure), and these aspects of the projects were documented at the time (Ardill 2018). By approximately 1940, successful revegetation outcomes had been achieved, although lists of restored plant species are not available. As well as the photograph presented below, further photographs from the period reveal that the stock exclosure technique achieved dramatic results at Whyalla beach: towering sandhills were successfully stabilised (see Gallery).

As at 2021, the Hummock Hill site was still public space, and could be readily inspected. Growth of locally indigenous vegetation appeared to be healthy. Although still public space, the Whyalla beach site, as pictured above, had been converted to a botanical garden, and largely featured introduced species.

Reference:

Ardill, P. J. (2018) ‘The South Australian arid zone plantation and natural regeneration work of Albert Morris’ September (Sydney: Australian Association of Bush Regenerators) https://www.aabr.org.au/morris-broken-hill/

Image courtesy of the BHP (Broken Hill Proprietary Company) Review.

Mining industry rehabilitation 1966

Members of the Noongar nation are the Traditional Owners of homelands extending throughout south-west Western Australia. Industrial company, Alcoa of Australia Limited commenced bauxite mining operations in the dry sclerophyll, biodiverse jarrah forests of these lands in 1963.

The first attempts to repair the mined land commenced in 1966 (Trigger et al. 2008), and they appear to represent the earliest known, documented mine site rehabilitation projects undertaken in Australia. Initially, and inappropriately, eucalyptus species of eastern Australian provenance were planted, but in subsequent projects, flora species typical of the jarrah forest have been introduced to the rehabilitation program. By ca.2000, the stated aim of the program was to establish a stable, self‐regenerating jarrah forest ecosystem designed to enhance or maintain water, timber, recreation, conservation, and other nominated forest values (Nichols et al. 2003).

Bibliography:

Nichols, O. G., Koch, J. M., Taylor, S., and Gardner, J. (1991) ‘Conserving biodiversity’ in Proceedings of the Australian Mining Industry Council Environmental Workshop Perth Australia 7–11 October 1991 pp.116-136

Nichols, O. G., Nichols, F. M. (2003) ‘Long-term trends in faunal recolonization after bauxite mining in the Jarrah forest of Southwestern Australia’ Restoration Ecology 11:3 261–272

Trigger, D., Mulcock, J., Gaynor, A., Toussaint, Y. (2008) ‘Ecological restoration, cultural preferences and the negotiation of ‘nativeness’ in Australia’ Geoforum 39 1273–1283

Government of Western Australia (2020) ‘Noongar History’ Department of the Premier and Cabinet Government of Western Australia https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-the-premier-and-cabinet/noongar-history

Image courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia (SLWA)

——–